By: Jordan Auzenne

Photos from: Getty Images / Kevork Djansezian; Solange Knowles; Chris Pizzello/Invision/AP

Oscar’s Sunday 2017 was a foggy morning, but the weather matched the date. While I waited in line at Starbucks, actor and producer Tracee Ellis Ross seemed to confirm the overcast on my timeline, as she donned a grey sweatshirt, hood on, with the name “TRAYVON” written big, black and capital. It was February 26th, the 5th anniversary of his death. Yet almost as soon as the photo was posted, several commented that it wasn’t the Hollywood elite’s job to call the rest of us out, to “fix her makeup and get ready to celebrate herself”. I grabbed my black coffee and got to work.

The role of Black people in the media has always been a complicated one. As the Pew Research Center explained in 2016, African Americans only make up 5.5% of those in newsrooms, sets, and stages across America. Yet as Black artists like Ellis Ross attempt to use their platform to progress the narrative of blackness, they are being shut down. It’s clear that as Black culture and aesthetics are being featured in media now more than ever, we want to enjoy Black work, so long as they stay quiet.

The timeliest example of this is Queen Bey. Black history month kicked off with a brilliant exhibition of Black strength, beauty and artistry as Beyoncé announced her pregnancy, in a photo that would later become the most liked on Instagram. Immediately, outlets like VOX, Elle and even Cosmopolitan were quick to admonish her. One writer even argued that “Beyoncé alienates other women who wish to be pregnant”, completely overlooking her (and Black women’s) history of miscarriage.

What garnered the most backlash was her performance at the Grammy’s on Feb.12th, in which she donned a golden halo and bejeweled dress, giving off Virgin Mary vibes. As PBS speculated, her embodiment of Oshun, a Yoruba water goddess of “female sensuality, love and fertility,” was meant to pay respect to Black womanhood. But while columnists grappled with their conceptions of sacrilege, they missed an incredible point: that Beyoncé could be used as a performance, but not honored as an artist.

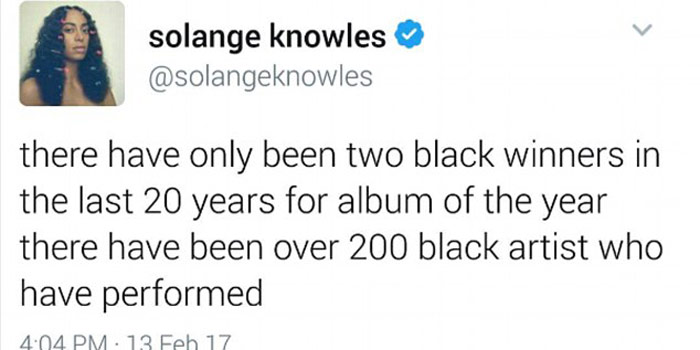

Beyoncé lost Album of the Year for the second time, to the fabulous and formidable Adele. As her younger sister, Solange, tweeted, “there have only been two black winners in the last 20 years for album of the year[.] there have been over 200 black artists who have performed”. She elucidates what several of us are realizing, that the music industry knows how powerful Beyoncé, and other artists like Kendrick, Kanye, and Nicki, have become. They recognize their influence in the community and their ability to innovate and redefine music, but only so far as to utilize their performance for viewership, then hand the award to someone else.

This cycle of exploitation occurs just as frequently in Hollywood, where certain movies can revolve around the concept of jazz without any recognition of the Black people who created it. Which is why the Academy Awards felt surreal this year. Even my RTF colleagues who adored La La Land admittedly agreed that a feel-good movie about Hollywood nostalgia shouldn’t be awarded over a film traversing the turmoil of intersectionality, of Black manhood and Black sexuality, a movie (FINALLY) where the characters weren’t either slaves or maids. What Moonlight accomplished was monumental. The low-budget indie film turned $1.5 million into $25, with an all-Black cast (including a fellow Longhorn), and little advertising. The anticipation going into Oscar’s Sunday was therefore unbearable.

The Academy Awards were in all sense of the phrase a “must see”. After 3 and a half hours, La La Land was initially announced as Best Picture, and as crew worked to fix the mistake, host Jimmy Kimmel “wanted to see [La La Land] win too”, arguing that “there are plenty of awards to go around.” It was producer Jordan Horowitz who mustered Adele-like grace, replying: “I’m going to be really proud to hand this to my friends at Moonlight.” But even in their accomplishment, they were overshadowed by whiteness.

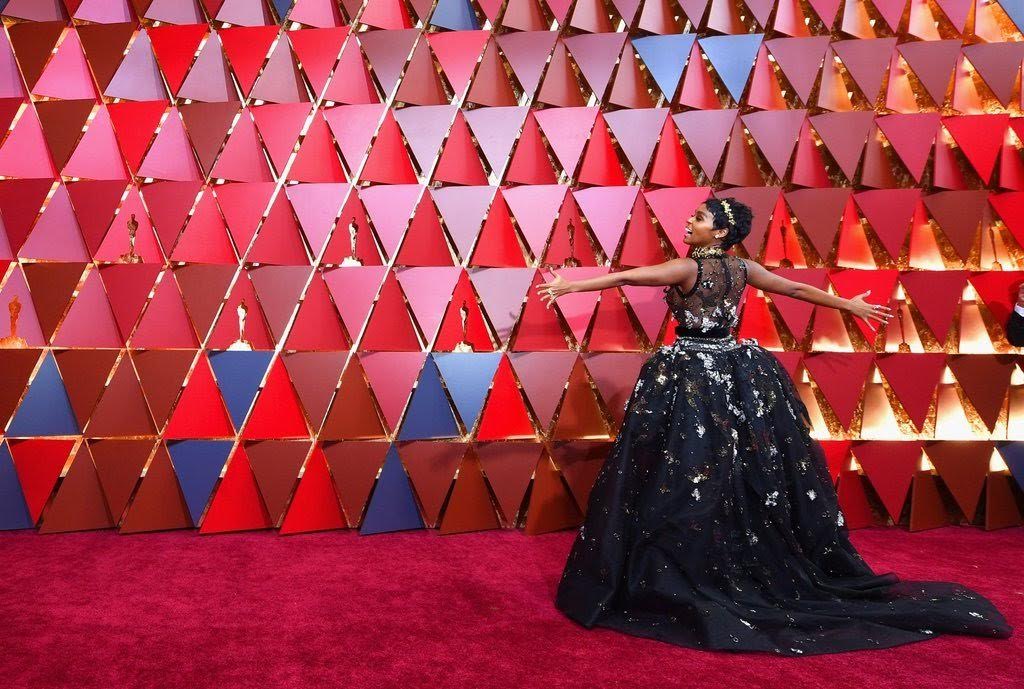

As Bustle articulated this morning, “This should have been a moment for people of color…for LGBTQ individuals, for people living in marginalized communities. This should have been a moment for their stories to be celebrated and seen, and instead it was a moment that turned into a punchline.” Moonlight had time to vouch for both of the films, forgive the Academy, and leave the stage. People will talk about how happy they are that they won. Or maybe how Lion or Manchester should have. They’ll talk about how wonderful Janelle Monáe looked. But we’ll never talk about the speech, because it didn’t happen. Bustle continues, “We shouldn’t have been laughing. We should have been applauding, and then holding the Academy to the responsibility of maintaining or exceeding this standard next year.”

Yet, it’s still peculiar. How in 90 years, the Oscar’s made this mistake. Still peculiar how Black artists are remembered for amazing performances, but never awards. In a time where media is being threatened more than ever before, where media is the foundation of understanding people who are far away and different from us, it’s peculiar how it keeps getting whiter.

Blay, Zeba. “Beyoncé Has Always Been Political — You Just Didn’t Notice.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 09 Feb. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2017.

Griffiths, Kadeen. “‘Moonlight’ May Have Won For Best Picture, But It Still Got Robbed.” Bustle. Bustle, 27 Feb. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2017.

Mettler, Katie. “The African, Hindu and Roman Goddesses Who Inspired Beyoncé’s Stunning Grammy Performance.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 13 Feb. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2017.

Midgette, Anne. “Beyoncé and the Apotheosis of the Pregnancy Announcement.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 02 Feb. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2017.

Moore, Suzanne. “The Oscars Mix-up Matters Because This Night Was Always about Racial Bias.” First Thoughts. Guardian News and Media, 27 Feb. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2017.

Vogt, Nancy. “African American News Media: Fact Sheet.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. N.p., 15 June 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2017.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Texas Speech team.